To model wind around an aircraft wing, gravitational pull on satellites, or magnetic forces between poles, we use vector fields.

In essence, a vector field is a direction and magnitude assigned to every point in space.

More practically though, vector fields represent either motion itself, or what drives it such as a force.

There are three main approaches to visualize motion:

- We can divide space with sample points and show where each point is being pulled and how strongly. This is done with arrows.

- We can also show how an element with a mass moves when carried by the flow, which is done via particles.

- Or we can trace the paths a massless particle would follow through the field, with flow lines.

Rendering vector fields in 2D is fairly straightforward.

In 3D on AR glasses, however, we need to satisfy a few constraints:

-

The geometry must look consistent from all viewing angles. A volumetric line shouldn’t look flat from certain directions.

-

The geometry must adapt to its spatial context, which in this case is the direction and magnitude sampled at a spatial location. Importing static or pre-animated 3D objects wouldn’t allow this kind of adaptivity, which means we must generate the geometry procedurally.

-

It must run smoothly in real time, while looking believable, so we need a minimal rendering procedure.

The most straightforward approach to render 3D lines is to generate tubes with capped ends. In Lens Studio, we can do this via the MeshBuilder API, which we first explored in our article on color spaces.

If the normals are encoded correctly (which requires having proper vertex ordering), GPU interpolation provides smooth color transitions across the tube surface and endcaps, which yields a believable look with minimal geometry.

The animation below illustrates the construction process:

Deforming 3D lines has an added difficulty of preserving the volume of the tube. If we just offset point positions by the same vector, we end up with wrong endcaps.

The solution is to compute a moving coordinate frame along the path. At each point, we calculate:

- a Tangent (T) vector: The direction the tube is heading (derivative of the path)

- a Normal (N) vector: Perpendicular to the tangent

- a Binormal (B) vector: Cross product of tangent and normal

Each vertex is then positioned using: p = center + (cos θ · N + sin θ · B) · radius

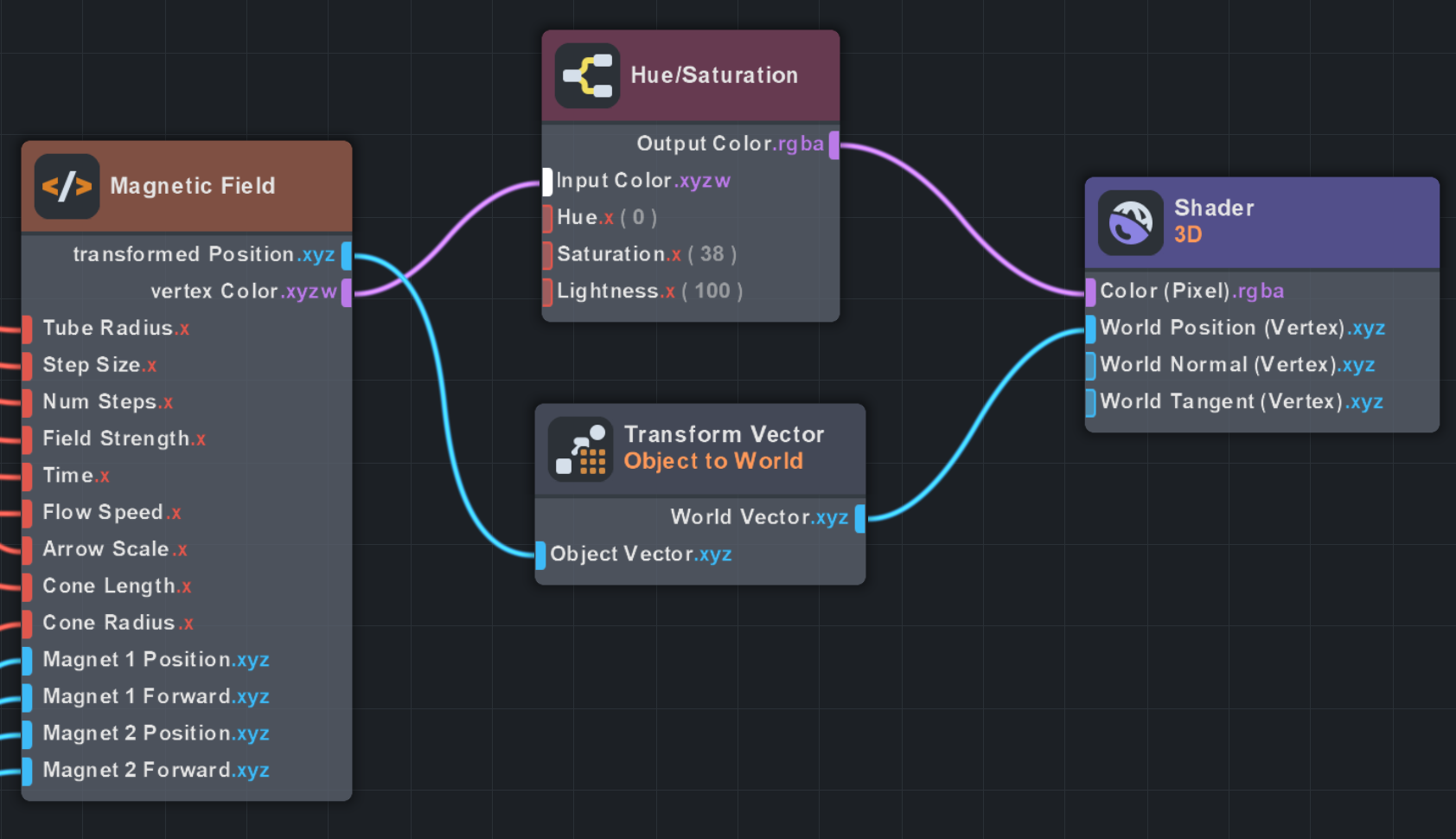

A key node from the material editor to make everything work is the Object to World converter. This transforms our computed vertex positions from object space into world space, ensuring the deformed tubes render correctly regardless of the object’s transform. Since you’re here, I might as well recommend you another node: Hue/Saturation. Lens Studio renders low value colors as transparent, so by using this node you can adjust the value color channel independently. It’s also useful for making colors pop by raising saturation.

I implemented a test example in Lens Studio and deployed it on Spectacles. Performance was satisfactory, so I continued with this approach.

Here’s the workflow for this test example in Lens Studio:

With tube generation and deformation working, we can now trace paths through a vector field.

Starting from sample points, we integrate by repeatedly querying the field at the current position and stepping in that direction.

Each step updates the tube’s frame, bending it along the flow.

Different field patterns produce vastly different flow lines.

3.1 Contraction

Vectors spiral inward toward a target point, creating sink-like behavior.

Fig 3.1a: Field visualization showing contraction flow pattern

Fig 3.1b: Demo on Spectacles

3.2 Expansion

Radial waves emanate outward from the target with 3D oscillation perpendicular to the flow.

Fig 3.2a: Field visualization showing expansion flow pattern

Fig 3.2b: Demo on Spectacles

3.3 Circulation

A 3D swirling vortex that mixes rotation in multiple planes around the target.

Fig 3.3a: Field visualization showing circulation flow pattern

Fig 3.3b: Demo on Spectacles

3.4 Vortex

Rotating cellular patterns with an added spin component based on angular position.

Fig 3.4a: Field visualization showing vortex flow pattern

Fig 3.4b: Demo on Spectacles

3.5 Waves

Sinusoidal interference patterns where each axis oscillates based on the other two coordinates.

Fig 3.5a: Field visualization showing wave interference pattern

Fig 3.5b: Demo on Spectacles

3.6 Implementation Workflow

The complete workflow connects a TypeScript component that generates procedural tube geometry with a custom shader that integrates the vector field on the GPU:

The field patterns above are mathematical abstractions. For something more concrete, we can model a magnetic dipole field, the kind you’ve probably seen with iron filings around bar magnets.

Each dipole creates a vector field based on its magnetic moment and the displacement from the dipole:

The field magnitude falls off as the inverse cube of distance: .

To trace flow lines through this field, we use Euler integration: starting from a sample point , we repeatedly query the field and step in its direction:

where is the normalized field direction and is the step size. Combining two dipoles produces the characteristic looping field lines.

The dipole formula translates directly to GPU code:

vec3 dipoleMagneticField(vec3 point, vec3 dipolePos, vec3 moment) {

vec3 r = point - dipolePos;

float dist = length(r);

if (dist < 0.1) {

return moment * FieldStrength * 2.0; // Inside dipole

} else {

vec3 rHat = r / dist; // r̂ = r/|r|

float dist3 = dist * dist * dist; // r³

float mDotR = dot(moment, rHat); // m · r̂

vec3 B = (3.0 * mDotR * rHat - moment) / dist3; // B = (3(m·r̂)r̂ - m) / r³

return B * FieldStrength;

}

}

Euler integration runs in the vertex shader, stepping each vertex along the field:

for (int i = 0; i < 64; i++) {

if (i >= clampedStepIndex) break;

prevPos = pos;

pos += getMagneticField(pos) * StepSize; // p_{n+1} = p_n + B(p_n) · Δs

}

Fig 4.1: Magnetic field visualization showing dipole field computation and integration

Fig 4.2: Demo on Spectacles with interactive magnet positioning

4.1 Implementation Workflow

The magnetic field implementation uses the same tube mesh generation approach but with a physically-based dipole field formula in the shader:

4.2 Visualization Modes

This implementation supports three visualization modes that can be toggled at runtime:

- Arrows: Static vectors showing direction and magnitude at discrete sample points. Best for understanding local field behavior.

- Trails: Tubes that follow field lines by integrating through the field. Shows how the field flows through space.

- Particles: Animated points that advect along the field, revealing the dynamic nature of the flow.

Demo showing the three visualization modes: arrows, flow lines, and particles

To ensure smooth performance on Spectacles and avoid freezes from unintentionally high geometry counts, I’ve defined a vertex budget (32K vertices per mesh). All procedural geometry settings automatically adapt to fit within this budget.

I’ve also defined Level of Detail (LOD) presets accessible via the settings panel, controlling:

- Radial segments: Cross-section smoothness (4 = square-ish, 8 = round)

- Length segments: Curve fidelity and field integration steps

- Grid size: Spatial density of field samples (e.g., 6³ = 216 tubes, 8³ = 512 tubes)

Among the three visualization modes, Trails is the most expensive due to many length segments per tube, while Particles uses minimal geometry (just 2 rings + caps per tube). Arrows mode has no flow animation overhead since it’s static.

To give users a visual hint of the active preset, I rendered a 2D version of each vector field with color-mapped direction and magnitude: hue encodes angle, saturation/brightness encodes strength.

Examples of fields with color discontinuities at singular points

Getting smooth gradients required careful attention to continuity in the field functions, both spatially (no jumps in color) and temporally (smooth animation).

2D color-mapped visualizations of each vector field preset

Adding an alpha falloff:

Contraction

Expansion

Circulation

Vortex

Waves

Magnetic

Animated previews with radial alpha falloff

Finally, I packed all frames into a sprite sheet:

Contraction

Expansion

Circulation

Vortex

Waves

Magnetic

Click any sprite sheet to expand

The final shader samples the correct frame based on elapsed time, computing UV coordinates into the grid. It also supports smooth blending between presets.

Material graph for the animated sprite sheet shader

Final Words

I hope this exploration of vector fields in AR encourages you to leverage them in your projects, or just make something fun with procedural geometry.

Motion is something I’m very passionate about. Having a framework to visualize it in real-time on AR glasses opens up possibilities I hadn’t considered before.

What I’m most excited about is using vector fields to manipulate data. Thanks to hand and body tracking input, I have a feeling that vector fields could become a full-fledged UI element category for XR applications.

Before getting into these considerations though, I’ll need to conclude my series on AR painting assistants, where I’ll use what I’ve learned from this project to push my experimentation with more fluid and cohesive UI elements.

If you want to try the project yourself, grab the source code or scan the Snapcode at the top to experience it on Spectacles.